Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the origin of the Anglican tradition, with foundational doctrines being contained in the Thirty-nine Articles and The Books of Homilies.[2] Its adherents are called Anglicans.

English Christianity traces its history to the Christian hierarchy recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain by the 3rd century and to the 6th-century Gregorian mission to Kent led by Augustine of Canterbury. It renounced papal authority in 1534, when King Henry VIII failed to secure a papal annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. The English Reformation accelerated under the regents of his successor, King Edward VI, before a brief restoration of papal authority under Queen Mary I and King Philip. The guiding theologian that shaped Anglican doctrine was the Reformer Thomas Cranmer, who developed the Church of England's liturgical text, the Book of Common Prayer.[2] The Act of Supremacy 1558 renewed the breach, and the Elizabethan Settlement (implemented 1559–1563) concluded the English Reformation, charting a course for the English church to describe itself as a via media between two branches of Protestantism—Lutheranism and Calvinism—and later, a denomination that is both Reformed and Catholic.[3]

In the earlier phase of the English Reformation there were both Roman Catholic martyrs and Protestant martyrs. The later phases saw the Penal Laws punish Roman Catholics and nonconforming Protestants. In the 17th century, the Puritan and Presbyterian factions continued to challenge the leadership of the church, which under the Stuarts veered towards a more Catholic interpretation of the Elizabethan Settlement, especially under Archbishop Laud. After the victory of the Parliamentarians, the Book of Common Prayer was abolished and the Presbyterian and Independent factions dominated. The episcopacy was abolished in 1646 but the Restoration restored the Church of England, episcopacy and the Book of Common Prayer.

Since the English Reformation, the Church of England has used the English language in the liturgy. As a broad church, the Church of England contains several doctrinal strands: the main traditions are known as Anglo-Catholic, high church, central church, and low church, the latter producing a growing evangelical wing that includes Reformed Anglicanism, with a smaller number of Arminian Anglicans.[4] Tensions between theological conservatives and liberals find expression in debates over the ordination of women and homosexuality. The British monarch (currently Charles III) is the supreme governor and the archbishop of Canterbury (vacant since 12 November 2024, after the resignation of Justin Welby) is the most senior cleric.

The governing structure of the church is based on dioceses, each presided over by a bishop. Within each diocese are local parishes. The General Synod of the Church of England is the legislative body for the church and comprises bishops, other clergy and laity. Its measures must be approved by the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

History

[edit]Middle Ages

[edit]

There is evidence for Christianity in Roman Britain as early as the 3rd century. After the fall of the Roman Empire, England was conquered by the Anglo-Saxons, who were pagans, and the Celtic church was confined to Cornwall and Wales.[5] In 597, Pope Gregory I sent missionaries to England to Christianise the Anglo-Saxons. This mission was led by Augustine, who became the first archbishop of Canterbury. The Church of England considers 597 the start of its formal history.[6][7][8]

In Northumbria, Celtic missionaries competed with their Roman counterparts. The Celtic and Roman churches disagreed over the date of Easter, baptismal customs, and the style of tonsure worn by monks.[9] King Oswiu of Northumbria summoned the Synod of Whitby in 664. The king decided Northumbria would follow the Roman tradition because Saint Peter and his successors, the bishops of Rome, hold the keys of the kingdom of heaven.[10]

By the late Middle Ages, Catholicism was an essential part of English life and culture. The 9,000 parishes covering all of England were overseen by a hierarchy of deaneries, archdeaconries, dioceses led by bishops, and ultimately the pope who presided over the Catholic Church from Rome.[11] Catholicism taught that the contrite person could cooperate with God towards their salvation by performing good works (see synergism).[12] God's grace was given through the seven sacraments.[13] In the Mass, a priest consecrated bread and wine to become the body and blood of Christ through transubstantiation. The church taught that, in the name of the congregation, the priest offered to God the same sacrifice of Christ on the cross that provided atonement for the sins of humanity.[14][15] The Mass was also an offering of prayer by which the living could help souls in purgatory.[16] While penance removed the guilt attached to sin, Catholicism taught that a penalty still remained. It was believed that most people would end their lives with these penalties unsatisfied and would have to spend time in purgatory. Time in purgatory could be lessened through indulgences and prayers for the dead, which were made possible by the communion of saints.[17]

Reformation

[edit]In 1527, Henry VIII was desperate for a male heir and asked Pope Clement VII to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. When the pope refused, Henry used Parliament to assert royal authority over the English church. In 1533, Parliament passed the Act in Restraint of Appeals, barring legal cases from being appealed outside England. This allowed the Archbishop of Canterbury to annul the marriage without reference to Rome. In November 1534, the Act of Supremacy formally abolished papal authority and declared Henry Supreme Head of the Church of England.[18]

Henry's religious beliefs remained aligned to traditional Catholicism throughout his reign, albeit with reformist aspects in the tradition of Erasmus and firm commitment to royal supremacy. In order to secure royal supremacy over the church, however, Henry allied himself with Protestants, who until that time had been treated as heretics.[19] The main doctrine of the Protestant Reformation was justification by faith alone rather than by good works.[20] The logical outcome of this belief is that the Mass, sacraments, charitable acts, prayers to saints, prayers for the dead, pilgrimage, and the veneration of relics do not mediate divine favour. To believe they can would be superstition at best and idolatry at worst.[21][22]

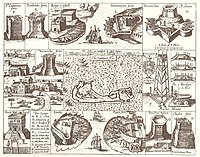

Between 1536 and 1540, Henry engaged in the dissolution of the monasteries, which controlled much of the richest land. He disbanded religious houses, appropriated their income, disposed of their assets, and provided pensions for the former residents. The properties were sold to pay for the wars. Historian George W. Bernard argues:

The dissolution of the monasteries in the late 1530s was one of the most revolutionary events in English history. There were nearly 900 religious houses in England, around 260 for monks, 300 for regular canons, 142 nunneries and 183 friaries; some 12,000 people in total, 4,000 monks, 3,000 canons, 3,000 friars and 2,000 nuns....one adult man in fifty was in religious orders.[23]

In the reign of Edward VI (1547–1553), the Church of England underwent an extensive theological reformation. Justification by faith was made a central teaching.[24] Government-sanctioned iconoclasm led to the destruction of images and relics. Stained glass, shrines, statues, and roods were defaced or destroyed. Church walls were whitewashed and covered with biblical texts condemning idolatry.[25] The most significant reform in Edward's reign was the adoption of an English liturgy to replace the old Latin rites.[26] Written by the Protestant Reformer Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, the 1549 Book of Common Prayer implicitly taught justification by faith,[27] and rejected the Catholic doctrines of transubstantiation and the sacrifice of the Mass.[28] This was followed by a greatly revised 1552 Book of Common Prayer, which propounded a Reformed view of the Lord's Supper (cf. Lord's Supper in Reformed theology).[29] Along with The Book of Common Prayer, The Thirty-nine Articles and The Books of Homilies, assembled through the efforts of the Reformer Thomas Cranmer, became the basis of Anglican doctrine after the English Reformation.[2]

During the reign of Mary I (1553–1558), England was briefly reunited with the Catholic Church. Mary died childless, so it was left to the new regime of her half-sister Queen Elizabeth I to resolve the direction of the Church. The Elizabethan Religious Settlement returned the Church to where it stood in 1553 before Edward's death. The Act of Supremacy made the monarch the Church's Supreme Governor of the Church of England. The Act of Uniformity restored a slightly altered 1552 Book of Common Prayer. In 1571, the Thirty-nine Articles received parliamentary approval as a doctrinal statement for the Church. The settlement ensured the Church of England was Protestant, but it was unclear what kind of Protestantism was being adopted.[30] Anglicanism was said to be a via media between two forms of Protestantism, Lutheranism and Reformed Christianity though more aligned with the latter than the former.[3] The prayer book's Reformed eucharistic theology posited a real spiritual presence (pneumatic presence), since Article 28 of the Thirty-nine Articles taught that the body of Christ was eaten "only after an heavenly and spiritual manner".[31][29] Nevertheless, there was enough ambiguity to allow later theologians to articulate various versions of Anglican eucharistic theology.[32]

The Church of England was the established church (constitutionally established by the state with the head of state as its supreme governor). The exact nature of the relationship between church and state would be developed over the next century.[33][34][35] Notably, the Act of Settlement 1701, which remains in force today, stipulates that the monarch (who serves as the Supreme Governor of the Church of England) be a Protestant, maintain the Protestant succession, and "join in communion with the Church of England as by law established."[36] The Coronation Oath Act 1688 (reiterated in the Act of Settlement 1701) requires the rising Sovereign to take an oath to maintain "the true Profession of the Gospel and the Protestant Reformed Religion Established by Law" in the United Kingdom.[36]

Stuart period

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2020) |

Struggle for control of the church persisted throughout the reigns of James I and his son Charles I, culminating in the outbreak of the First English Civil War in 1642. The two opposing factions consisted of Puritans, who sought to "purify" the church and enact more far-reaching Protestant reforms, and those who wanted to retain traditional beliefs and practices. In a period when many believed "true religion" and "good government" were the same thing, religious disputes often included a political element, one example being the struggle over bishops. In addition to their religious function, bishops acted as state censors, able to ban sermons and writings considered objectionable, while lay people could be tried by church courts for crimes including blasphemy, heresy, fornication and other 'sins of the flesh', as well as matrimonial or inheritance disputes.[37] They also sat in the House of Lords and often blocked legislation opposed by the Crown; their ousting from Parliament by the 1640 Clergy Act was a major step on the road to war.[38]

Following Royalist defeat in 1646, the episcopacy was formally abolished.[39] In 1649, the Commonwealth of England outlawed a number of former practices and Presbyterian structures replaced the episcopate. The Thirty-nine Articles were replaced by the Westminster Confession. Worship according to the Book of Common Prayer was outlawed and replace by the Directory of Public Worship. Despite this, about one quarter of English clergy refused to conform to this form of state presbyterianism.[citation needed] It was also opposed by religious Independents who rejected the very idea of state-mandated religion, and included Congregationalists like Oliver Cromwell, as well as Baptists, who were especially well represented in the New Model Army.[40]

After the Stuart Restoration in 1660, Parliament restored the Church of England to a form not far removed from the Elizabethan version. Until James II of England was ousted by the Glorious Revolution in November 1688, many Nonconformists still sought to negotiate terms that would allow them to re-enter the church.[41] In order to secure his political position, William III of England ended these discussions and the Tudor ideal of encompassing all the people of England in one religious organisation was abandoned. The religious landscape of England assumed its present form, with the Anglican established church occupying the middle ground and Nonconformists continuing their existence outside. One result of the Restoration was the ousting of 2,000 parish ministers who had not been ordained by bishops in the apostolic succession or who had been ordained by ministers in presbyter's orders. Official suspicion and legal restrictions continued well into the 19th century. Roman Catholics, perhaps 5% of the English population (down from 20% in 1600) were grudgingly tolerated, having had little or no official representation after the Pope's excommunication of Queen Elizabeth in 1570, though the Stuarts were sympathetic to them. By the end of 18th century they had dwindled to 1% of the population, mostly amongst upper middle-class gentry, their tenants, and extended families.[citation needed]

Union with the Church of Ireland

[edit]By the Fifth Article of the Union with Ireland 1800, the Church of England and Church of Ireland were united into "one Protestant Episcopal church, to be called, the United Church of England and Ireland".[42] Although "the continuance and preservation of the said united church ... [was] deemed and taken to be an essential and fundamental part of the union",[43] the Irish Church Act 1869 separated the Irish part of the church again and disestablished it, the Act coming into effect on 1 January 1871.

Overseas developments

[edit]

As the English Empire (after the 1707 union of the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, the British Empire) expanded, English (after 1707, British) colonists and colonial administrators took the established church doctrines and practices together with ordained ministry and formed overseas branches of the Church of England.

The Diocese of Nova Scotia was created on 11 August 1787 by Letters Patent of George III which "erected the Province of Nova Scotia into a bishop's see" and these also named Charles Inglis as first bishop of the see.[44] The diocese was the first Church of England see created outside England and Wales (i.e. the first colonial diocese). At this point, the see covered present-day New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Quebec.[45] From 1825 to 1839, it included the nine parishes of Bermuda, subsequently transferred to the Diocese of Newfoundland.[46]

As they developed, beginning with the United States of America, or became sovereign or independent states, many of their churches became separate organisationally, but remained linked to the Church of England through the Anglican Communion. In the provinces that made up Canada, the church operated as the "Church of England in Canada" until 1955 when it became the Anglican Church of Canada.[47]

In Bermuda, the oldest remaining British overseas possession, the first Church of England services were performed by the Reverend Richard Buck, one of the survivors of the 1609 wreck of the Sea Venture which initiated Bermuda's permanent settlement. The nine parishes of the Church of England in Bermuda, each with its own church and glebe land, rarely had more than a pair of ordained ministers to share between them until the 19th century. From 1825 to 1839, Bermuda's parishes were attached to the See of Nova Scotia. Bermuda was then grouped into the new Diocese of Newfoundland and Bermuda from 1839. In 1879, the Synod of the Church of England in Bermuda was formed. At the same time, a Diocese of Bermuda became separate from the Diocese of Newfoundland, but both continued to be grouped under the Bishop of Newfoundland and Bermuda until 1919, when Newfoundland and Bermuda each received its own bishop.[citation needed] The Church of England in Bermuda was renamed in 1978 as the Anglican Church of Bermuda, which is an extra-provincial diocese,[48] with both metropolitan and primatial authority coming directly from the Archbishop of Canterbury. Among its parish churches is St Peter's Church in the UNESCO World Heritage Site of St George's Town, which is the oldest Anglican church outside of the British Isles, and the oldest Protestant church in the New World.[49]

The Church of India, Burma and Ceylon was established in Colonial India, with its first diocese being erected in 1813, the Diocese of Calcutta. Indian bishops were present at the first Lambeth Conference.[50]

The first Anglican missionaries arrived in Nigeria in 1842 and the first Anglican Nigerian was consecrated a bishop in 1864. However, the arrival of a rival group of Anglican missionaries in 1887 led to infighting that slowed the Church's growth. In this large African colony, by 1900 there were only 35,000 Anglicans, about 0.2% of the population. However, by the late 20th century the Church of Nigeria was the fastest growing of all Anglican churches, reaching about 18 percent of the local population by 2000.[47]

The church established its presence in Hong Kong and Macau in 1843. In 1951, the Diocese of Hong Kong and Macao became an extra-provincial diocese, and in 1998 it became a province of the Anglican Communion, under the name Hong Kong Sheng Kung Hui.

From 1796 to 1818 the Church began operating in Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon), following the 1796 start of British colonisation, when the first services were held for the British civil and military personnel. In 1799, the first Colonial Chaplain was appointed, following which CMS and SPG missionaries began their work, in 1818 and 1844 respectively. Subsequently the Church of Ceylon was established: in 1845 the diocese of Colombo was inaugurated, with the appointment of James Chapman as Bishop of Colombo. It served as an extra-provincial jurisdiction of the archbishop of Canterbury, who served as its metropolitan.

Early 21st century

[edit]Deposition from holy orders overturned

[edit]Under the guidance of Rowan Williams and with significant pressure from clergy union representatives, the ecclesiastical penalty for convicted felons to be defrocked was set aside from the Clergy Discipline Measure 2003. The clergy union argued that the penalty was unfair to victims of hypothetical miscarriages of criminal justice, because the ecclesiastical penalty is considered irreversible. Although clerics can still be banned for life from ministry, they remain ordained as priests.[51]

Continued decline in attendance and church response

[edit]

Bishop Sarah Mullally has insisted that declining numbers at services should not necessarily be a cause of despair for churches, because people may still encounter God without attending a service in a church; for example hearing the Christian message through social media sites or in a café run as a community project.[52] Additionally, 9.7 million people visit at least one of its churches every year and 1 million students are educated at Church of England schools (which number 4,700).[53] In 2019, an estimated 10 million people visited a cathedral and an additional "1.3 million people visited Westminster Abbey, where 99% of visitors paid / donated for entry".[54] In 2022, the church reported than an estimated 5.7 million people visited a cathedral and 6.8 million visited Westminster Abbey.[55] Nevertheless, the archbishops of Canterbury and York warned in January 2015 that the Church of England would no longer be able to carry on in its current form unless the downward spiral in membership were somehow to be reversed, as typical Sunday attendance had halved to 800,000 in the previous 40 years:[56]

The urgency of the challenge facing us is not in doubt. Attendance at Church of England services has declined at an average of one per cent per annum over recent decades and, in addition, the age profile of our membership has become significantly older than that of the population... Renewing and reforming aspects of our institutional life is a necessary but far from sufficient response to the challenges facing the Church of England. ... The age profile of our clergy has also been increasing. Around 40 per cent of parish clergy are due to retire over the next decade or so.

Between 1969 and 2010, almost 1,800 church buildings, roughly 11% of the stock, were closed (so-called "redundant churches"); the majority (70%) in the first half of the period; only 514 being closed between 1990 and 2010.[57] Some active use was being made of about half of the closed churches.[58] By 2019 the rate of closure had steadied at around 20 to 25 per year (0.2%); some being replaced by new places of worship.[59] Additionally, in 2018 the church announced a £27 million growth programme to create 100 new churches.[60]

Low salaries

[edit]In 2015 the Church of England admitted that it was embarrassed to be paying staff under the living wage. The Church of England had previously campaigned for all employers to pay this minimum amount. The archbishop of Canterbury acknowledged it was not the only area where the church "fell short of its standards".[61]

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]The COVID-19 pandemic had a sizeable effect on church attendance, with attendance in 2020 and 2021 well below that of 2019. By 2022, the first full year without substantial restrictions related to the pandemic, numbers were still notably down on pre-pandemic participation. According to the 2022 release of "Statistics for Mission" by the church, the median size of each church's worshipping community (those who attend in person or online at least once a month) stood at 37 people, with average weekly attendance having declined from 34 to 25; while Easter and Christmas services had seen falls from 51 to 38 and 80 to 56 individuals respectively.[62] In the following year's release the Church detailed that, compared to pre-pandemic trends, the Church's average weekly attendance was 8% below what was expected. However, attendance at particular services such as baptisms and marriages had increased by more than 20% compared to the projected pre-pandemic trend.[63]

Examples of wider declines across the whole church include:[62][63]

| Estimated change, 2019 to 2020 | Estimated change, 2019 to 2021 | Estimated change, 2019 to 2022 | Estimated change, 2019 to 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worshipping community | −7% | −13% | −12% | -10% |

| All-age average weekly attendance (October) | −60% | −29% | −23% | -20% |

| All-age average Sunday attendance (October) | −53% | −28% | −23% | -20% |

| Easter attendance | N/A | −56% | −27% | -20% |

| Christmas attendance | −79% | −58% | −30% | -16% |

Doctrine and practice

[edit]

Thomas Cranmer, the guiding Protestant Reformer who shaped Anglican doctrine after the English Reformation, was instrumental in the compilation of the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion, Book of Common Prayer and Books of Homilies.[2][64] The canon law of the Church of England identifies the Christian scriptures as the source of its doctrine. In addition, doctrine is also derived from the teachings of the Church Fathers and ecumenical councils (as well as the ecumenical creeds) in so far as these agree with scripture. This doctrine is expressed in the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion, the Book of Common Prayer, and the Ordinal containing the rites for the ordination of deacons, priests, and the consecration of bishops.[65] Richard Hooker's appeal to scripture as the primary source of Christian doctrine, informed by church tradition, and reason, has been influential in hermeneutics.[66]

The Church of England's doctrinal character today is largely the result of the Elizabethan Settlement. The historical development of Anglicanism saw itself as navigating a via media between two forms of Protestantism—Lutheranism and Reformed Christianity—though leaning closer to the latter than the former.[3][67] The Church of England affirms the protestant reformation principle that scripture contains all things necessary to salvation and is the final arbiter in doctrinal matters. The Thirty-nine Articles are the church's only official confessional statement. The Church of England did retain three orders of ministry and the apostolic succession of bishops, as with the Scandinavian Lutheran Churches (such as the Church of Sweden) and Roman Catholicism. Its identity has thus been described as Reformed and Catholic.[3] There are differences of opinion within the Church of England over the necessity of episcopacy. Some consider it essential, while others feel it is needed for the proper ordering of the church.[66] The Bible, the Creeds, Apostolic Order, and the administration of the Sacraments are sufficient to establish catholicity. The Protestant Reformation in England was initially much concerned about doctrine but the Elizabethan Settlement tried to put a stop to doctrinal contentions. The proponents of further changes, nonetheless, tried to get their way by making changes in Church Order (abolition of bishops), governance (Canon Law) and liturgy. They did not succeed because the monarchy and the Church resisted and the majority of the population were indifferent. Moreover, "despite all the assumptions of the Reformation founders of that Church, it had retained a catholic character." The existence of cathedrals "without substantial alteration" and "where the "old devotional world cast its longest shadow for the future of the ethos that would become Anglicanism,"[68] This is "One of the great mysteries of the English Reformation,"[68] that there was no complete break with the past but a muddle that was per force turned into a virtue.[69]

The Church of England has, as one of its distinguishing marks, a breadth of opinion from liberal to conservative clergy and members.[70] This tolerance has allowed Anglicans who emphasise the catholic tradition and others who emphasise the reformed tradition to coexist. The three schools of thought (or parties) in the Church of England are sometimes called high church (or Anglo-Catholic), low church (or evangelical Anglican) and broad church (or liberal). The high church party places importance on the Church of England's continuity with the pre-Reformation Catholic Church, adherence to ancient liturgical usages and the sacerdotal nature of the priesthood. As their name suggests, Anglo-Catholics maintain many traditional catholic practices and liturgical forms.[71] The Catholic tradition, strengthened and reshaped from the 1830s by the Oxford movement, has stressed the importance of the visible Church and its sacraments and the belief that the ministry of bishops, priests and deacons is a sign and instrument of the Church of England's Catholic and apostolic identity.[72] The low church party is more Protestant in both ceremony and theology.[73] It has emphasized the significance of the Protestant aspects of the Church of England's identity, stressing the importance of the authority of Scripture, preaching, justification by faith and personal conversion.[72] The theological perspectives within the Church of England have included the Reformed Anglican perspective, as well as a minority Arminian Anglican view.[4] Historically, the term 'broad church' has been used to describe those of middle-of-the-road ceremonial preferences who lean theologically towards liberal protestantism.[74] The liberal broad church tradition has emphasized the importance of the use of reason in theological exploration. It has stressed the need to develop Christian belief and practice in order to respond creatively to wider advances in human knowledge and understanding and the importance of social and political action in forwarding God's kingdom.[72] The balance between these strands of churchmanship is not static: in 2013, 40% of Church of England worshippers attended evangelical Anglican churches (compared with 26% in 1989), and 83% of very large congregations were evangelical. Such churches were also reported to attract higher numbers of men and young adults than others.[75]

Worship and liturgy

[edit]

In 1604, James I ordered an English language translation of the Bible known as the King James Version, which was published in 1611 and authorised for use in parishes, although it was not an "official" version per se.[76] The Church of England's official book of liturgy as established in English Law is the 1662 version of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP). In the year 2000, the General Synod approved a modern liturgical book, Common Worship, which can be used as an alternative to the BCP. Like its predecessor, the 1980 Alternative Service Book, it differs from the Book of Common Prayer in providing a range of alternative services, mostly in modern language, although it does include some BCP-based forms as well, for example Order Two for Holy Communion. (This is a revision of the BCP service, altering some words and allowing the insertion of some other liturgical texts such as the Agnus Dei before communion.) The Order One rite follows the pattern of more modern liturgical scholarship.[citation needed]

The liturgies are organised according to the traditional liturgical year and the calendar of saints. The sacraments of baptism and the eucharist are generally thought necessary to salvation. Infant baptism is practised. At a later age, individuals baptised as infants receive confirmation by a bishop, at which time they reaffirm the baptismal promises made by their parents or sponsors. The eucharist, consecrated by a thanksgiving prayer including Christ's Words of Institution, is believed to be "a memorial of Christ's once-for-all redemptive acts in which Christ is objectively present and effectually received in faith".[77]

The use of hymns and music in the Church of England has changed dramatically over the centuries. Traditional Choral evensong is a staple of most cathedrals. The style of psalm chanting harks back to the Church of England's pre-reformation roots. During the 18th century, clergy such as Charles Wesley introduced their own styles of worship with poetic hymns.[78]

In the latter half of the 20th century, the influence of the Charismatic Movement significantly altered the worship traditions of numerous Church of England parishes, primarily affecting those of evangelical persuasion. These churches now adopt a contemporary worship form of service, with minimal liturgical or ritual elements, and incorporating contemporary worship music.[79]

Just as the Church of England has a large conservative or "traditionalist" wing, it also has many liberal members and clergy. Approximately one third of clergy "doubt or disbelieve in the physical resurrection".[80] Others, such as Giles Fraser, a contributor to The Guardian, have argued for an allegorical interpretation of the virgin birth of Jesus.[81] The Independent reported in 2014 that, according to a YouGov survey of Church of England clergy, "as many as 16 per cent are unclear about God and two per cent think it is no more than a human construct."[82][83] Moreover, many congregations are seeker-friendly environments. For example, one report from the Church Mission Society suggested that the church open up "a pagan church where Christianity [is] very much in the centre" to reach out to spiritual people.[84]

The Church of England is launching a project on "gendered language" in Spring 2023 in efforts to "study the ways in which God is referred to and addressed in liturgy and worship".[85]

Women's ministry

[edit]Women were appointed as deaconesses from 1861, but they could not function fully as deacons and were not considered ordained clergy. Women have historically been able to serve as lay readers. During the First World War, some women were appointed as lay readers, known as "bishop's messengers", who also led missions and ran churches in the absence of men. After the war, no women were appointed as lay readers until 1969.[86]

Legislation authorising the ordination of women as deacons was passed in 1986 and they were first ordained in 1987. The ordination of women as priests was approved by the General Synod in 1992 and began in 1994. In 2010, for the first time in the history of the Church of England, more women than men were ordained as priests (290 women and 273 men),[87] but in the next two years, ordinations of men again exceeded those of women.[88]

In July 2005, the synod voted to "set in train" the process of allowing the consecration of women as bishops. In February 2006, the synod voted overwhelmingly for the "further exploration" of possible arrangements for parishes that did not want to be directly under the authority of a bishop who is a woman.[89] On 7 July 2008, the synod voted to approve the ordination of women as bishops and rejected moves for alternative episcopal oversight for those who do not accept the ministry of bishops who are women.[90] Actual ordinations of women to the episcopate required further legislation, which was narrowly rejected in a General Synod vote in November 2012.[91][92] On 20 November 2013, the General Synod voted overwhelmingly in support of a plan to allow the ordination of women as bishops, with 378 in favour, 8 against and 25 abstentions.[93]

On 14 July 2014, the General Synod approved the ordination of women as bishops. The House of Bishops recorded 37 votes in favour, two against with one abstention. The House of Clergy had 162 in favour, 25 against and four abstentions. The House of Laity voted 152 for, 45 against with five abstentions.[94] This legislation had to be approved by the Ecclesiastical Committee of the Parliament before it could be finally implemented at the November 2014 synod. In December 2014, Libby Lane was announced as the first woman to become a bishop in the Church of England. She was consecrated as a bishop in January 2015.[95] In July 2015, Rachel Treweek was the first woman to become a diocesan bishop in the Church of England when she became the Bishop of Gloucester.[96] She and Sarah Mullally, Bishop of Crediton, were the first women to be ordained as bishops at Canterbury Cathedral.[96] Treweek later made headlines by calling for gender-inclusive language, saying that "God is not to be seen as male. God is God."[97]

In May 2018, the Diocese of London consecrated Dame Sarah Mullally as the first woman to serve as the Bishop of London.[98] Bishop Sarah Mullally occupies the third most senior position in the Church of England.[99] Mullally has described herself as a feminist and will ordain both men and women to the priesthood.[100] She is also considered by some to be a theological liberal.[101] On women's reproductive rights, Mullally describes herself as pro-choice while also being personally pro-life.[102] On marriage, she supports the current stance of the Church of England that marriage is between a man and a woman, but also said that: "It is a time for us to reflect on our tradition and scripture, and together say how we can offer a response that is about it being inclusive love."[103]

Same-sex unions and LGBT clergy

[edit]The Church of England has been discussing same-sex marriages and LGBT clergy.[104][105] The church holds that marriage is a union of one man with one woman.[106][107] The church does not allow clergy to perform same-sex marriages, but in February 2023 approved of blessings for same-sex couples following a civil marriage or civil partnership.[108][109] The church teaches "Same-sex relationships often embody genuine mutuality and fidelity."[110][111] In January 2023, the Bishops approved "prayers of thanksgiving, dedication and for God's blessing for same-sex couples."[112][113][114] The commended prayers of blessing for same-sex couples, known as "Prayers of Love and Faith," may be used during ordinary church services, and in November 2023 General Synod voted to authorise "standalone" blessings for same-sex couples on a trial basis, while permanent authorisation will require additional steps.[115][116] The church also officially supports celibate civil partnerships; "We believe that Civil Partnerships still have a place, including for some Christian LGBTI couples who see them as a way of gaining legal recognition of their relationship."[117]

Civil partnerships for clergy have been allowed since 2005, so long as they remain sexually abstinent,[118][119][120] and the church extends pensions to clergy in same-sex civil partnerships.[121] In a missive to clergy, the church communicated that "there was a need for committed same-sex couples to be given recognition and 'compassionate attention' from the Church, including special prayers."[122] "There is no prohibition on prayers being said in church or there being a 'service'" after a civil union.[123] After same-sex marriage was legalised, the church sought continued availability of civil unions, saying "The Church of England recognises that same-sex relationships often embody fidelity and mutuality. Civil partnerships enable these Christian virtues to be recognised socially and legally in a proper framework."[124] In 2024, the General Synod voted in support of eventually permitting clergy to enter into civil same-sex marriages.[125][126]

In 2014, the bishops released guidelines that permit "more informal kind of prayer" for couples.[127] In the guidelines, "gay couples who get married will be able to ask for special prayers in the Church of England after their wedding, the bishops have agreed."[110] In 2016, the bishop of Grantham, Nicholas Chamberlain, announced that he is gay, in a same-sex relationship and celibate, becoming the first bishop to do so in the church.[128] The church had decided in 2013 that gay clergy in civil partnerships so long as they remain sexually abstinent could become bishops.[120][129] "The House [of Bishops] has confirmed that clergy in civil partnerships, and living in accordance with the teaching of the church on human sexuality, can be considered as candidates for the episcopate."[130]

In 2017, the House of Clergy voted against the motion to "take note" of the bishops' report defining marriage as between a man and a woman.[131] Due to passage in all three houses being required, the motion was rejected.[132] After General Synod rejected the motion, the archbishops of Canterbury and York called for "radical new Christian inclusion" that is "based on good, healthy, flourishing relationships, and in a proper 21st century understanding of being human and of being sexual."[133] The church officially opposes "conversion therapy", a practice which attempts to change a gay or lesbian person's sexual orientation, calling it unethical and supports the banning of "conversion therapy" in the UK.[134][135] The Diocese of Hereford approved a motion calling for the church "to create a set of formal services and prayers to bless those who have had a same-sex marriage or civil partnership."[136] In 2022, "The House [of Bishops] also agreed to the formation of a Pastoral Consultative Group to support and advise dioceses on pastoral responses to circumstances that arise concerning LGBTI+ clergy, ordinands, lay leaders and the lay people in their care."[137]

Regarding transgender issues, the 2017 General Synod voted in favour of a motion saying that transgender people should be "welcomed and affirmed in their parish church".[138][139] The motion also asked the bishops "to look into special services for transgender people."[140][141] The bishops initially said "the House notes that the Affirmation of Baptismal Faith, found in Common Worship, is an ideal liturgical rite which trans people can use to mark this moment of personal renewal."[142] The Bishops also authorised services of celebration to mark a gender transition that will be included in formal liturgy.[143][144] Transgender people may marry in the Church of England after legally making a transition.[145] "Since the Gender Recognition Act 2004, trans people legally confirmed in their gender identity under its provisions are able to marry someone of the opposite sex in their parish church."[146] The church further decided that same-gender couples may remain married when one spouse experiences gender transition provided that the spouses identified as opposite genders at the time of the marriage.[147][148] Since 2000, the church has allowed priests to undergo gender transition and remain in office.[149] The church has ordained openly transgender clergy since 2005.[150] The Church of England ordained the church's first openly non-binary priest.[151][152]

In January 2023, a meeting of the Bishops of the Church of England rejected demands for clergy to conduct same-sex marriages. However, proposals would be put to the General Synod that clergy should be able to hold church blessings for same-sex civil marriages, albeit on a voluntary basis for individual clergy. This comes as the Church continued to be split on same-sex marriages.[153]

In February 2023, ten archbishops of the Global South Fellowship of Anglican Churches released a statement stating that they had broken communion and no longer recognised Justin Welby as "the first among equals" or "primus inter pares" in the Anglican Communion in response to the General Synod's decision to approve the blessing of same-sex couples following a civil marriage or partnership, leading to questions as to the status of the Church of England as the mother church of the international Anglican Communion.[154][155][156]

In November 2023, the General Synod narrowly voted to allow church blessings for same-sex couples on a trial basis.[157] In December 2023, the first blessings of same-sex couples began in the Church of England.[158][159] In 2024, the General Synod voted to support moving forward with "stand-alone" services of blessing for same-sex couples after a civil marriage or civil partnership.[160][161][162]

Bioethics issues

[edit]The Church of England is generally opposed to abortion but believes "there can be strictly limited conditions under which abortion may be morally preferable to any available alternative".[163] The church also opposes euthanasia. Its official stance is that "While acknowledging the complexity of the issues involved in assisted dying/suicide and voluntary euthanasia, the Church of England is opposed to any change in the law or in medical practice that would make assisted dying/suicide or voluntary euthanasia permissible in law or acceptable in practice." It also states that "Equally, the Church shares the desire to alleviate physical and psychological suffering, but believes that assisted dying/suicide and voluntary euthanasia are not acceptable means of achieving these laudable goals."[164] In 2014, George Carey, a former archbishop of Canterbury, announced that he had changed his stance on euthanasia and now advocated legalising "assisted dying".[165] On embryonic stem-cell research, the church has announced "cautious acceptance to the proposal to produce cytoplasmic hybrid embryos for research".[166]

In the 19th century, English law required the burial of people who had died by suicide to occur only between the hours of 9 p.m. and midnight and without religious rites.[167] The Church of England permitted the use of alternative burial services for people who had died by suicide. In 2017, the Church of England changed its rules to permit the full, standard Christian burial service regardless of whether a person had died by suicide.[168]

Social work

[edit]Church Urban Fund

[edit]The Church of England set up the Church Urban Fund in the 1980s to tackle poverty and deprivation. It sees poverty as trapping individuals and communities with some people in urgent need, leading to dependency, homelessness, hunger, isolation, low income, mental health problems, social exclusion and violence. They feel that poverty reduces confidence and life expectancy and that people born in poor conditions have difficulty escaping their disadvantaged circumstances.[169]

Child poverty

[edit]In parts of Liverpool, Manchester and Newcastle two-thirds of babies are born to poverty and have poorer life chances, also a life expectancy 15 years lower than babies born in the best-off fortunate communities.[170]

The deep-rooted unfairness in our society is highlighted by these stark statistics. Children being born in this country, just a few miles apart, couldn't witness a more wildly differing start to life. In child poverty terms, we live in one of the most unequal countries in the western world. We want people to understand where their own community sits alongside neighbouring communities. The disparity is often shocking but it's crucial that, through greater awareness, people from all backgrounds come together to think about what could be done to support those born into poverty. [Paul Hackwood, the Chair of Trustees at Church Urban Fund][171]

Action on hunger

[edit]Many prominent people in the Church of England have spoken out against poverty and welfare cuts in the United Kingdom. Twenty-seven bishops are among 43 Christian leaders who signed a letter which urged David Cameron to make sure people have enough to eat.

We often hear talk of hard choices. Surely few can be harder than that faced by the tens of thousands of older people who must 'heat or eat' each winter, harder than those faced by families whose wages have stayed flat while food prices have gone up 30% in just five years. Yet beyond even this we must, as a society, face up to the fact that over half of people using food banks have been put in that situation by cutbacks to and failures in the benefit system, whether it be payment delays or punitive sanctions.[172]

Thousands of UK citizens use food banks. The church's campaign to end hunger considers this "truly shocking" and called for a national day of fasting on 4 April 2014.[172]

Membership

[edit]As of 2009[update], the Church of England estimated that it had approximately 25 - 26 million baptised members – about 47% of the English population.[173][174] This number has remained consistent since 2001 and was cited again in 2013 and 2014.[175][176][177] In 2010, the government estimated that there were 24,841,000 baptised members of the Church of England.[174] According to a 2016 study published by the Journal of Anglican Studies, the Church of England continued to claim 26 million baptised members, while it also had approximately 1.7 million active baptised members.[178][179][180] Due to its status as the established church, in general, anyone may be married, have their children baptised or their funeral in their local parish church, regardless of whether they are baptised or regular churchgoers.[181]

Between 1890 and 2001, churchgoing in the United Kingdom declined steadily.[182] In the years 1968 to 1999, Anglican Sunday church attendances almost halved, from 3.5 percent of the population to 1.9 per cent.[183] By 2014, Sunday church attendances had declined further to 1.4 per cent of the population.[184] One study published in 2008 suggested that if current trends continued, Sunday attendances could fall to 350,000 in 2030 and 87,800 in 2050.[185] The Church of England releases an annual publication, Statistics for Mission, detailing numerous criteria relating to participation with the church. Below is a snapshot of several key metrics from every five years since 2001 (2022 has been used in place of 2021 to avoid the impact of Covid restrictions). Since 2021 Sunday Church attendance has increased, although not to pre-pandemic levels. [186]

| Category | 2001[187] | 2006[187] | 2011[188] | 2016[188] | 2022[189][c] | 2023[190] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worshipping Community[d] | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1,138,800 | 984,000 | 1,007,000 |

| All Age Weekly Attendance | 1,205,000 | 1,163,000 | 1,050,300 | 927,300 | 654,000 | 693,000 |

| All Age Sunday Attendance | 1,041,000 | 983,000 | 858,400 | 779,800 | 547,000 | 574,000 |

| Easter Attendance | 1,593,000 | 1,485,000 | 1,378,200 | 1,222,700 | 861,000 | 938,000 |

| Christmas Attendance | 2,608,000 | 2,994,000 | 2,641,500 | 2,580,000 | 1,622,000 | 1,961,000 |

Personnel

[edit]In 2020, there were almost 20,000 active clergy serving in the Church of England, including 7,200 retired clergy who continued to serve. In that year, 580 were ordained (330 in stipendiary posts and 250 in self-supporting parochial posts) and a further 580 ordinands began their training.[191] In that year, 33% of those in ordained ministry were female, an increase from the 26% reported in 2016.[191]

Structure

[edit]

Article XIX ('Of the Church') of the Thirty-nine Articles defines the church as follows:

The visible Church of Christ is a congregation of faithful men, in which the pure Word of God is preached, and the sacraments be duly ministered according to Christ's ordinance in all those things that of necessity are requisite to the same.[192]

The British monarch has the constitutional title of Supreme Governor of the Church of England. The canon law of the Church of England states, "We acknowledge that the King's most excellent Majesty, acting according to the laws of the realm, is the highest power under God in this kingdom, and has supreme authority over all persons in all causes, as well ecclesiastical as civil."[193] In practice this power is often exercised through Parliament and on the advice of the Prime Minister.

The Church of Ireland and the Church in Wales separated from the Church of England in 1869[194] and 1920[195] respectively and are autonomous churches in the Anglican Communion; Scotland's national church, the Church of Scotland, is Presbyterian, but the Scottish Episcopal Church is part of the Anglican Communion.[196]

In addition to England, the jurisdiction of the Church of England extends to the Isle of Man, the Channel Islands and a few parishes in Flintshire, Monmouthshire and Powys in Wales which voted to remain with the Church of England rather than joining the Church in Wales.[197] Expatriate congregations on the continent of Europe have become the Diocese of Gibraltar in Europe.

The church is structured as follows (from the lowest level upwards):[citation needed]

- Parish is the most local level, often consisting of one church building (a parish church) and community, although many parishes are joining forces in a variety of ways for financial reasons. The parish is looked after by a parish priest who for historical or legal reasons may be called by one of the following offices: vicar, rector, priest in charge, team rector, team vicar. The first, second, fourth and fifth of these may also be known as the 'incumbent'. The running of the parish is the joint responsibility of the incumbent and the parochial church council (PCC), which consists of the parish clergy and elected representatives from the congregation. The Diocese of Gibraltar in Europe is not formally divided into parishes.

- There are a number of local churches that do not have a parish. In urban areas there are a number of proprietary chapels (mostly built in the 19th century to cope with urbanisation and growth in population). Also in more recent years there are increasingly church plants and fresh expressions of church, whereby new congregations are planted in locations such as schools or pubs to spread the Gospel of Christ in non-traditional ways.

- Deanery, e.g., Lewisham or Runnymede. This is the area for which a Rural Dean (or area dean) is responsible. It consists of a number of parishes in a particular district. The rural dean is usually the incumbent of one of the constituent parishes. The parishes each elect lay (non-ordained) representatives to the deanery synod. Deanery synod members each have a vote in the election of representatives to the diocesan synod.

- Archdeaconry, e.g., the seven in the Diocese of Gibraltar in Europe. This is the area under the jurisdiction of an archdeacon. It consists of a number of deaneries.

- Diocese, e.g., Diocese of Durham, Diocese of Guildford, Diocese of St Albans. This is the area under the jurisdiction of a diocesan bishop, e.g., the bishops of Durham, Guildford and St Albans, and will have a cathedral. There may be one or more suffragan bishops within the diocese who assist the diocesan bishop in his ministry, e.g., in Guildford diocese, the Bishop of Dorking. In some very large dioceses a legal measure has been enacted to create "episcopal areas", where the diocesan bishop runs one such area himself and appoints "area bishops" to run the other areas as mini-dioceses, legally delegating many of his powers to the area bishops. Dioceses with episcopal areas include London, Chelmsford, Oxford, Chichester, Southwark, and Lichfield. The bishops work with an elected body of lay and ordained representatives, known as the Diocesan Synod, to run the diocese. A diocese is subdivided into a number of archdeaconries.

- Province, i.e., Canterbury or York. This is the area under the jurisdiction of an archbishop, i.e. the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. Decision-making within the province is the responsibility of the General Synod (see also above). A province is subdivided into dioceses.

- Primacy, i.e., Church of England. The Archbishop of York's title of "Primate of England" is essentially honorific and carries with it no powers beyond those inherent in being Archbishop and Metropolitan of the Province of York.[198] The Archbishop of Canterbury, on the other hand, the "Primate of All England", has powers that extend over the whole of England, and also Wales—for example, through his Faculty Office he may grant a "special marriage licence" permitting the parties to marry otherwise than in a church: for example, in a school, college or university chapel;[199] or anywhere, if one of the parties to the intended marriage is in danger of imminent death.[200][e]

- Royal Peculiar, a small number of churches which are more closely associated with the Crown, for example Westminster Abbey, and a very few more closely associated with the law which although conforming to the rites of the Church, are outside episcopal jurisdiction.

All rectors and vicars are appointed by patrons, who may be private individuals, corporate bodies such as cathedrals, colleges or trusts, or by the bishop or directly by the Crown. No clergy can be instituted and inducted into a parish without swearing the Oath of Allegiance to His Majesty, and taking the Oath of Canonical Obedience "in all things lawful and honest" to the bishop. Usually they are instituted to the benefice by the bishop and then inducted by the archdeacon into the possession of the benefice property—church and parsonage. Curates (assistant clergy) are appointed by rectors and vicars, or if priests-in-charge by the bishop after consultation with the patron. Cathedral clergy (normally a dean and a varying number of residentiary canons who constitute the cathedral chapter) are appointed either by the Crown, the bishop, or by the dean and chapter themselves. Clergy officiate in a diocese either because they hold office as beneficed clergy or are licensed by the bishop when appointed, or simply with permission.[citation needed]

Primates

[edit]

The most senior bishop of the Church of England is the Archbishop of Canterbury, who is the metropolitan of the southern province of England, the Province of Canterbury. He has the status of Primate of All England. He is the focus of unity for the worldwide Anglican Communion of independent national or regional churches. Justin Welby has been Archbishop of Canterbury since the confirmation of his election on 4 February 2013.[201]

The second most senior bishop is the Archbishop of York, who is the metropolitan of the northern province of England, the Province of York. For historical reasons (relating to the time of York's control by the Danes)[202] he is referred to as the Primate of England. Stephen Cottrell became Archbishop of York in 2020.[203] The Bishop of London, the Bishop of Durham and the Bishop of Winchester are ranked in the next three positions, insofar as the holders of those sees automatically become members of the House of Lords.[204][f]

Diocesan bishops

[edit]The process of appointing diocesan bishops is complex, due to historical reasons balancing hierarchy against democracy, and is handled by the Crown Nominations Committee which submits names to the Prime Minister (acting on behalf of the Crown) for consideration.[205]

Representative bodies

[edit]The Church of England has a legislative body, General Synod. This can create two types of legislation, measures and canons. Measures have to be approved but cannot be amended by the British Parliament before receiving royal assent and becoming part of the law of England.[206] Although it is the established church in England only, its measures must be approved by both Houses of Parliament including the non-English members. Canons require Royal Licence and Royal Assent, but form the law of the church, rather than the law of the land.[207]

Another assembly is the Convocation of the English Clergy, which is older than the General Synod and its predecessor the Church Assembly. By the Synodical Government Measure 1969 almost all of the Convocations' functions were transferred to the General Synod. Additionally, there are Diocesan Synods and deanery synods, which are the governing bodies of the divisions of the Church.[citation needed]

House of Lords

[edit]Of the 42 diocesan archbishops and bishops in the Church of England, 26 are permitted to sit in the House of Lords. The Archbishops of Canterbury and York automatically have seats, as do the bishops of London, Durham and Winchester. The remaining 21 seats are filled in order of seniority by date of consecration. It may take a diocesan bishop a number of years to reach the House of Lords, at which point he or she becomes a Lord Spiritual. The Bishop of Sodor and Man and the Bishop of Gibraltar in Europe are not eligible to sit in the House of Lords as their dioceses lie outside the United Kingdom.[208]

Crown Dependencies

[edit]Although they are not part of England or the United Kingdom, the Church of England is also the established church in the Crown Dependencies of the Isle of Man, the Bailiwick of Jersey and the Bailiwick of Guernsey. The Isle of Man has its own diocese of Sodor and Man, and the Bishop of Sodor and Man is an ex officio member of the legislative council of the Tynwald on the island.[209] Historically the Channel Islands have been under the authority of the Bishop of Winchester, but this authority has temporarily been delegated to the Bishop of Dover since 2015. In Jersey the Dean of Jersey is a non-voting member of the States of Jersey. In Guernsey the Church of England is the established church, although the Dean of Guernsey is not a member of the States of Guernsey.[210]

Sex abuse

[edit]The 2020 report from the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse found several cases of sexual abuse within the Church of England, and concluded that the Church did not protect children from sexual abuse, and allowed abusers to hide.[211][212][213] The Church spent more effort defending alleged abusers than supporting victims or protecting children and young people.[211] Allegations were not taken seriously, and in some cases clergymen were ordained even with a history of child sex abuse.[214] Bishop Peter Ball was convicted in October 2015 on several charges of indecent assault against young adult men.[212][213][215]

In June 2023, the Archbishops' Council dismissed the three board members of the Independent Safeguarding Board, which was set up in 2021 "to hold the Church to account, publicly if needs be, for any failings which are preventing good safeguarding from happening". A statement issued by the Archbishops of Canterbury and York referred to there being "no prospect of resolving the disagreement and that it is getting in the way of the vital work of serving victims and survivors". Jasvinder Sanghera and Steve Reeves, the two independent members of the board, had complained about interference with their work by the Church.[216] The Bishop of Birkenhead, Julie Conalty, speaking to BBC Radio 4 in connection with the dismissals, said: "I think culturally we are resistant as a church to accountability, to criticism. And therefore I don't entirely trust the church, even though I'm a key part of it and a leader within it, because I see the way the wind blows is always in a particular direction."[217]

On 20 July 2023, it was announced that the archbishops of Canterbury and York had appointed Alexis Jay to provide proposals for an independent system of safeguarding for the Church of England.[218]

Funding and finances

[edit]Although an established church, the Church of England does not receive any direct government support, except some funding for building work. Donations comprise its largest source of income, and it also relies heavily on the income from its various historic endowments. In 2005, the Church of England had estimated total outgoings of around £900 million.[219]

The Church of England manages an investment portfolio which is worth more than £8 billion.[220]

Online church directories

[edit]The Church of England runs A Church Near You, an online directory of churches. A user-edited resource, it currently lists more than 16,000 churches and has 20,000 editors in 42 dioceses.[221] The directory enables parishes to maintain accurate location, contact and event information, which is shared with other websites and mobile apps. The site allows the public to find their local worshipping community, and offers churches free resources,[222] such as hymns, videos and social media graphics.

The Church Heritage Record includes information on over 16,000 church buildings, including architectural history, archaeology, art history, and the surrounding natural environment.[223] It can be searched by elements including church name, diocese, date of construction, footprint size, listing grade, and church type. The types of church identified include:

- Major Parish Church: "some of the most special, significant and well-loved places of worship in England", having "most of all" of the characteristics of being large (over 1,000msq), listed (generally grade I or II*), having "exceptional significance and/or issues necessitating a conservation management plan" and having a local role beyond that of an average parish church. As of December 2021[update] there are 312 such churches in the database.[224][225] These churches are eligible to join the Major Churches Network.

- Festival Church: a church not used for weekly services but used for occasional services and other events.[226] These churches are eligible to join the Association of Festival Churches.[227] As of December 2021[update] there are 19 such churches in the database.[228]

- CCT Church: a church under the care of the Churches Conservation Trust. As of December 2021[update] there are 345 such churches in the database.[229]

- Friendless Church: as of December 2021[update] there are 24 such churches in the database;[230] the Friends of Friendless Churches cares for 60 churches across England and Wales.[231]

See also

[edit]- Acts of Supremacy

- Apostolicae curae

- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- Anglican Communion sexual abuse cases

- Church Commissioners

- Church of England Newspaper

- Disestablishmentarianism

- Dissolution of the Monasteries

- English Covenant

- English Reformation

- Historical development of Church of England dioceses

- List of archdeacons in the Church of England

- List of bishops in the Church of England

- List of the first 32 women ordained as Church of England priests

- List of the largest Protestant bodies

- Mothers' Union

- Properties and finances of the Church of England

- Ritualism in the Church of England

- Women and the Church

Notes

[edit]- ^ Broad church (including variations of high church and low church)

- ^ With various theological and doctrinal identities, including Anglo-Catholic, Liberal and Evangelicals.

- ^ Using 2022 due to Covid restrictions in 2021

- ^ Attendance of at least once per month, first used after 2012

- ^ The powers to grant special marriage licences, to appoint notaries public, and to grant Lambeth degrees, are derived from the so called "legatine powers" which were held by the Pope's Legate to England prior to the Reformation, and were transferred to the Archbishop of Canterbury by the Ecclesiastical Licences Act 1533. Thus they are not, strictly speaking, derived from the status of the Archbishop of Canterbury as "Primate of All England". For this reason, they extend also to Wales.[198]

- ^ The bishops are named in this order in the section.

References

[edit]- ^ Church of England at World Council of Churches

- ^ a b c d Samuel, Chimela Meehoma (28 April 2020). Treasures of the Anglican Witness: A Collection of Essays. Partridge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5437-5784-2.

In addition to his emphasis on Bible reading and the introduction to the Book of Common Prayer, other media through which Cranmer sought to catechize the English people were the introduction of the First Book of Homilies and the 39 Articles of Religion. Together with the Book of Common Prayer and the Forty-Two Articles (which were later reduced to thirty-nine), the Book of Homilies stands as one of the essential texts of the Edwardian Reformation, and they all helped to define the shape of Anglicanism then, and in the subsequent centuries. More so, the Articles of Religion, whose primary shape and content were given by Archbishop Cranmer and Bishop Ridley in 1553 (and whose final official form was ratified by Convocation, the Queen, and Parliament in 1571), provided a more precise interpretation of Christian doctrine to the English people. According to John H. Rodgers, they "constitute the formal statements of the accepted, common teaching put forth by the Church of England as a result of the Reformation."

- ^ a b c d Anglican and Episcopal History. Historical Society of the Episcopal Church. 2003. p. 15.

Others had made similar observations, Patrick McGrath commenting that the Church of England was not a middle way between Roman Catholic and Protestant, but "between different forms of Protestantism", and William Monter describing the Church of England as "a unique style of Protestantism, a via media between the Reformed and Lutheran traditions". MacCulloch has described Cranmer as seeking a middle way between Zurich and Wittenberg but elsewhere remarks that the Church of England was "nearer Zurich and Geneva than Wittenberg.

- ^ a b Hampton, Stephen. "Anti-Arminians: The Anglican Reformed Tradition from Charles II to George I". The Gospel Coalition. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ Moorman 1973, pp. 3–4, 9.

- ^ "History of the Church of England". Church of England. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Booty, John E.; Sykes, Stephen; Knight, Jonathan, eds. (1998). Study of Anglicanism. London: Fortress Books. p. 477. ISBN 0-281-05175-5.

- ^ Delaney, John P. (1980). Dictionary of Saints (Second ed.). Garden City, NY: Doubleday. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-385-13594-8.

- ^ Moorman 1973, p. 19.

- ^ "Synod of Whitby | English Church history". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, p. 11.

- ^ MacCulloch 1996, p. 210.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, p. 7.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Hefling 2021, pp. 97–98.

- ^ MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2001). The Later Reformation in England, 1547–1603. British History in Perspective (2nd ed.). Palgrave. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780333921395.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Shagan 2017, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Shagan 2017, p. 32.

- ^ Hefling 2021, p. 96.

- ^ Hefling 2021, p. 97.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, p. 126.

- ^ G. W. Bernard, "The Dissolution of the Monasteries", History (2011) 96#324 p. 390.

- ^ Marshall 2017a, p. 308.

- ^ Duffy, Eamon (2005). The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, c. 1400 – c. 1580 (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. pp. 450–454 and 458. ISBN 978-0-300-10828-6.

- ^ Shagan 2017, pp. 41.

- ^ Jeanes, Gordon (2006). "Cranmer and Common Prayer". In Hefling, Charles; Shattuck, Cynthia (eds.). The Oxford Guide to the Book of Common Prayer: A Worldwide Survey. Oxford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-529756-0.

- ^ MacCulloch 1996, pp. 412, 414.

- ^ a b Strout, Shawn O. (29 February 2024). Of Thine Own Have We Given Thee: A Liturgical Theology of the Offertory in Anglicanism. James Clarke & Company. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-227-17995-6.

- ^ Marshall 2017b, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Marshall 2017b, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Marshall 2017b, p. 51.

- ^ Eberle, Edward J. (2011). Church and State in Western Society. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4094-0792-8. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

The Church of England later became the official state Protestant church, with the monarch supervising church functions.

- ^ Fox, Jonathan (2008). A World Survey of Religion and the State. Cambridge University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-521-88131-9. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

The Church of England (Anglican) and the Church of Scotland (Presbyterian) are the official religions of the UK.

- ^ Ferrante, Joan (2010). Sociology: A Global Perspective. Cengage Learning. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-8400-3204-1. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

the Church of England [Anglican], which remains the official state church

- ^ a b Doe, Norman; Coleman, Stephen (22 February 2024). The Legal History of the Church of England: From the Reformation to the Present. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-5099-7317-0.

- ^ Helmholz 2003, p. 102.

- ^ Wedgwood 1958, p. 31.

- ^ King 1968, pp. 523–537.

- ^ Spurr 1998, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Miller, John (1978). James II; A study in kingship. Menthuen. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-0413652904.

- ^ Pickering, Danby (1799). The Statutes at Large from the Magna Charta, to the End of the Eleventh Parliament of Great Britain, Anno 1761 [continued to 1806]. By Danby Pickering. J. Bentham. p. 653.

- ^ "An Act for the Union of Great Britain and Ireland 1800 – Article Fifth (sic)". Archived from the original on 24 March 2018.

- ^ "No. 12910". The London Gazette. 7 August 1787. p. 373.

- ^ Diocesan site – History Archived 16 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 31 December 2012)

- ^ Piper, Liza (2000). "The Church of England". Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador. Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ a b Miranda Threlfall-Holmes (2012). The Essential History of Christianity. SPCK. pp. 133–134. ISBN 9780281066438.

- ^ "Member Churches". anglicancommunion.org.

- ^ "Welcome to St Peter's Church in St. George's, Bermuda". St Peter's. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Tovey, Phillip (30 August 2017). Anglican Baptismal Liturgies. Canterbury Press. p. 234. ISBN 9781786220202.

- ^ Bingham, John (13 July 2015). "Church of England could return to defrocking rogue priests after child abuse scandals". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ Bingham, John (9 June 2015). "Empty pews not the end of the world, says Church of England's newest bishop". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Facts and Stats of The Church of England". Church of England. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ "Key areas of research". The Church of England. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ Staff writer (13 April 2023). "Cathedral visitor numbers rebound after pandemic". www.christiantoday.com. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ "Church of England cannot carry on as it is unless decline 'urgently' reversed – Welby and Sentamu", The Daily Telegraph, 12 January 2015.

- ^ "Closed Churches Division". Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Closed churches". The Church of England.

- ^ "Church of England announces 100 new churches in £27 million growth programme". www.anglicannews.org.

- ^ "Church of England: Justin Welby says low pay 'embarrassing'". BBC News.

- ^ a b "Statistics for Missions 2022" (PDF). Church of England. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Statistics for Mission 2023" (PDF). Church of England. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Jensen, Michael P. (7 January 2015). "9 Things You Should Really Know About Anglicanism". The Gospel Coalition. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

The theology of the founding documents of the Anglican church—the Book of Homilies, the Book of Common Prayer, and the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion—expresses a theology in keeping with the Reformed theology of the Swiss and South German Reformation. It is neither Lutheran, nor simply Calvinist, though it resonates with many of Calvin's thoughts.

- ^ Canon A5. Canons of the Church of England Archived 25 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Shepherd, Jr. & Martin 2005, pp. 349–350.

- ^ Robinson, Peter (2 August 2012). "The Reformed Face of Anglicanism". The Old High Churchman. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

Cranmer's personal journey of faith left its mark on the Church of England in the form of a Liturgy that remains to this day more closely allied to Lutheran practice, but that liturgy is couple to a doctrinal stance that is broadly, but decidedly Reformed. ... The 42 Articles of 1552 and the 39 Articles of 1563, both commit the Church of England to the fundamentals of the Reformed Faith. Both sets of Articles affirm the centrality of Scripture, and take a monergist position on Justification. Both sets of Articles affirm that the Church of England accepts the doctrine of predestination and election as a 'comfort to the faithful' but warn against over much speculation concerning that doctrine. Indeed a casual reading of the Wurttemburg Confession of 1551, the Second Helvetic Confession, the Scots Confession of 1560, and the XXXIX Articles of Religion reveal them to be cut from the same bolt of cloth.

- ^ a b MacCulloch 1990, p. 79.

- ^ MacCulloch 1990, p. 142.

- ^ Brown, Andrew (13 July 2014). "Liberalism increases as power shifts to the laity in the Church of England". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "High Church", New Catholic Encyclopedia, 2nd ed., vol. 6 (Detroit: Gale, 2003), pp. 823–824.

- ^ a b c "History of the Church of England". The Church of England. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Low Church", New Catholic Encyclopedia, 2nd ed., vol. 8 (Detroit: Gale, 2003), p. 836.

- ^ E. McDermott, "Broad Church", New Catholic Encyclopedia, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (Detroit: Gale, 2003), pp. 624–625.

- ^ 'New Directions', May 2013

- ^ Cowart & Knappen 2007, p. ?.

- ^ Shepherd, Jr. & Martin 2005, p. 350.

- ^ "BBC – Religions – Christianity: Charles Wesley". BBC. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "A Charismatic Invasion of Anglicanism? | Dale M. Coulter". First Things. 7 January 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ Petre, Jonathan. "One third of clergy do not believe in the Resurrection". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "The story of the virgin birth runs against the grain of Christianity". The Guardian. 24 December 2015. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Survey finds 2 per cent of Anglican priests are not believers". The Independent. 27 October 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "YouGov / University of Lancaster and Westminster Faith Debates" (PDF). YouGov. 23 October 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Church of England creating 'pagan church' to recruit members". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Is God They/Them? Church of England considers gender-neutral pronouns". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ tojsiab. "Church of England इतिहास देखें अर्थ और सामग्री – hmoob.in". www.hmoob.in. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "More new women priests than men for first time". The Daily Telegraph. 4 February 2012. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Arnett, George (11 February 2014). "How much of the Church of England clergy is female?". The Guardian.

- ^ Church votes overwhelmingly for compromise on women bishops. Ekklesia.

- ^ "Church will ordain women bishops". BBC News. 7 July 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ Pigott, Robert. (14 February 2009) Synod struggles on women bishops. BBC News.

- ^ "Church of England general synod votes against women bishops", BBC News, 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Church of England Synod votes overwhelmingly in support of women bishops". The Descrier. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ "LIVE: Vote backs women bishops". BBC. 14 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "After turmoil, Church of England consecrates first woman bishop". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ a b First female diocesan bishop in C of E consecrated. Anglicannews.org. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Sherwood, Harriet (24 October 2015). "'God is not a he or a she', says first female bishop to sit in House of Lords". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "First woman Bishop of London installed". www.churchtimes.co.uk. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ "First female Bishop of London installed". BBC News. 12 May 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.